Risk can often seem like a straightforward, black-and-white concept: it’s something that might happen, with a probability attached. For example, there’s a 5% chance it might rain today, so if you happen to be outside in the open there is a 5% chance you might get wet. Up until the moment the rain actually starts, it remains a risk – something uncertain. But as soon as the first drop hits your head, that risk has become an event.

Of course, what qualifies as “rain” and “getting wet” can vary depending on where you are. In the Netherlands, it takes a proper downpour to earn the label, while in Italy or Spain, even a few drops might have people scrambling for cover. But whether it’s rain or “not quite rain,” water falling from the sky will leave you wet. So, in the end, risk is less about shades of gray and more about black or white – or perhaps, more aptly, dry or wet.

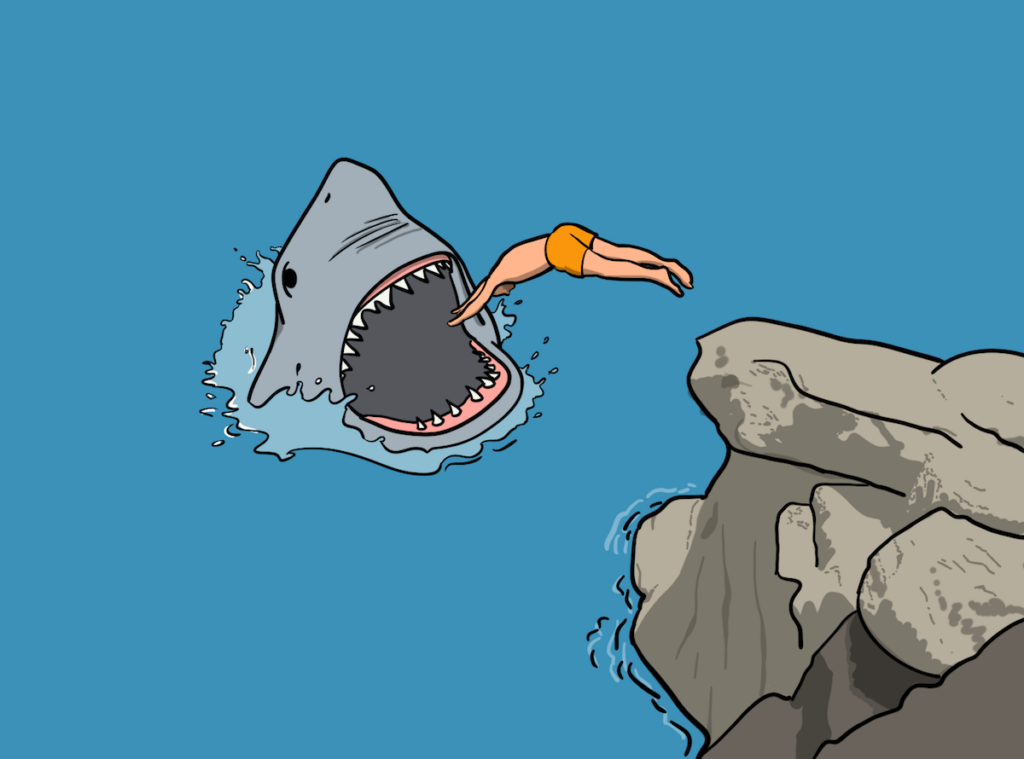

Project management isn’t always so black and white. Take me, for instance, in the header cartoonist illustration – jumping off a cliff. Technically, there’s a risk I might get wet. A very decent risk. However, if I actually were in a cartoon, the odds of getting wet would not be as clear, and largely depend on whether it made for a good punchline. Take Tom & Jerry’s Cat Fishin’ from 1947. Tom is fishing, and Jerry is the bait. At 2:10 min, Jerry, tied to the end of a fishing line, hurtles toward the water. Just before hitting the water, Jerry pulls a break and comes to a hold. He tests the water, finds it too cold, and swiftly makes his way back – no wet fur, no frostbite, just effortless cool.

I’ve tried that trick myself, and let me tell you: it’s a lot harder than it looks. John Flach once invited me to visit a small pond in the nearby mountains and maybe take a swim. The water was above freezing – barely – but still cold enough to make you question your life choices. I still remember the moment mid-air, as if time slowed down. Suspended between sky and lake, I thought, What am I doing? Can I undo this? Spoiler: I could not.

Now, technically, as I hung there, you could argue there was only a risk of getting wet. After all, a giant fish might have surfaced and caught me before I hit the water. If this were a cartoon, that scenario might even be the most likely outcome. And in that freezing moment, suspended above the mountain pond, the idea had its charm – warmth, albeit with a side of fishy drama, it seemed like a reasonable trade-off. But alas, the fish stayed put, and gravity, ever dependable, did what gravity does best. Yes, there was a risk of getting wet, but let’s face it – the odds were flirting with a solid 100%.

Of course, it hadn’t been 100% all day. As mentioned, when I woke up, the chance of getting wet was a modest 5%, mostly due to the potential for rain. Then came breakfast, and with it, John’s fateful invite to visit the pond. That nudged the odds somewhat upwards. And then me packing my swimming shorts pushed the probability to a confident 80%. Up until the point of takeoff from the rock, we could still talk about risk with some degree of uncertainty. But the moment I launched into the air, the equation changed. Even if, technically the event of getting wet had not happened yet at that point, getting wet wasn’t a risk anymore – it was a certainty.

In project management, this kind of scenario is all too common. If your timeline has shrunk to the point where the gap between finishing development and the release date is barely enough to start testing – let alone complete all 113 test cases – you’re no longer dealing with a risk of delay. At that stage, delay is a foregone conclusion. Similarly, if 20% of your database is riddled with duplicate entries, poor data quality isn’t a risk – it’s an undeniable reality. When you’ve reached this point, gathering everyone for a risk assessment session to debate the possibility of missing tests or encountering data quality issues is like trying to board a train that left the station hours ago. The moment for pondering risks has passed. Hopefully, you were savvy enough to prepare an action plan when you saw the station approaching. Now is the time to dust off that plan, give it a quick sanity check, and roll it out before things derail entirely.

You probably know all this already, so you might be wondering: “What’s your point?” Honestly, I asked myself the same question. Maybe this is just a bit of stress relief after yet another so-called risk meeting that should have been a call to action.

But it reminded me of two old truths:

- First, if the meeting isn’t about potential impacts and probabilities (where the average probability is less than 100%), then it’s not a risk meeting – no matter what it says on the invite or the agenda.

- Second, the real challenge is recognizing when a risk has crossed the line into foregone certainty and then responding appropriately. Risk management isn’t just about identifying and debating potential problems; it is also about knowing when to stop analyzing and start doing.

So, yes. Standing at the edge of the pond in swim shorts, there is a risk I might get wet, and risk management still applies – unless, of course, I’ve already jumped. Even if the event of me hitting the water hasn’t happened yet, it’s no longer risk management; it’s splash management.