When I started working at the faculty of industrial design in pursue of my doctorate, I was amazed about how ‘designers’ had the ability to create ideas out of thin air that were beautiful but also – as any engineer like myself could explain – were completely impossible to realise. I soon observed that they also would invariably find someone or someway to realise and test these ideas, and I came to appreciate that being unconstrained about what is seemingly possible actually is a precious talent, or maybe even a gift.

Nowadays, design thinking seems to be all about empathy, and understanding the customer. You’re be surprised how often when asking candidates about their experience with design thinking they replied with “Yeah sure, I have created a few personas once.” Even educators appear to share this view; see for example the small clip showing Hani Asfour, Dean from the Dubai Institute of Design & Innovation, explaining what is special about design thinking, just as an example of what I am regularly confronted with.

To me, this suggest that you could take any old waterfall process, add some more empathy to the requirements elicitation phase, et voila, you have a design thinking approach. That conflicts with my experience and understanding.

Kees Overbeeke later explained that exploring what you could do (as opposed to what you can do) is how designers think, how they explore challenges. Basically

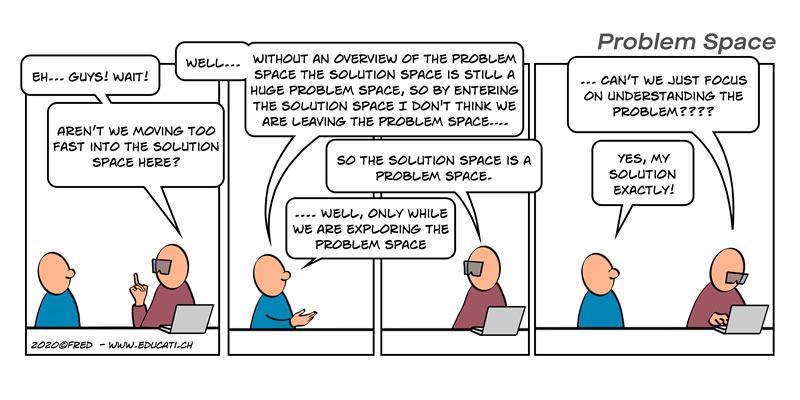

Engineers have a different approach. Engineers are trained to think in a more straight forward approach; first analyse the problem, then design the solution. This is how you create bridges. How you build rockets. How you produce all the stuff we use in our daily life. By contrast, designers analyse the problem by designing a solution. “Does this work?” “What do you think about this?” “You know, what you could do is…” every ‘design’ creating a new point of view on the challenge, creating more clarity in both understanding the challenge and in defining what would be an acceptable solution. For designers, there is no sequential separation between problem and solution space, but an iterative hopping back and forth, exploring both at the same time.

For me, even now years later, I find it difficult if not virtually impossible to ignore constraints of technical solutions, and go beyond my limited view of what is possible to try and focus on discovering what is desirable independent from what (I know) is possible.

An engineering approach works well especially in situations where the problem space and solution space are known, but less so-called in case of wicked problems; problems that are fluid, that are incomplete, contradictory, with changing requirements, and difficult to grasp and pin-down. These are the type of problems where the designer’s approach of trying and testing if it works, are successful.

The Designers’ approach has been formalised in the Design Thinking process, as for illustrated by the above process and described by the Interaction Design Foundation, but to me it appears to be a linear Engineering approach with a bit more designers tools.

What for me is essential. and seems to have been lost, is the approach of exploring the problem and the solution space in harmony; Design Thinking embracing a yin-yang relationship or problem and solution, and addressing both in harmony.