“There doesn’t seem to be much value in claiming something doesn’t exist” my son said when I told him that systems don’t exist. Fair point. So, let’s unpack that wisdom. What does it really mean to say systems don’t exist? And why stop at systems? Are we even talking just about systems? Do we exist? Do you? Do I? What if this whole reality is just the product of an overactive and overactive imagination? “Wow,” my son said, “… then we must have a pretty wild imagination!” Another fair point. So, like the philosophers before us, I guess I’ll concede—we exist. I am… I think. Or something like that.

So, what’s the deal with systems not existing? First, what exactly is a system? According to Russell Ackoff, a system is a collection of two or more parts, where none of the parts possesses the same properties as the whole and none has independent control over it. Take a vehicle, for instance. It’s more than just a collection of parts. No single essential component controls the whole. The engine, for example, won’t run without the battery, and the car can’t move without the wheels. In short, it’s a system. A vehicle is a system designed to get you from A to B. Interestingly, the vehicle as a whole can do that, but good luck asking any single part to manage it. The engine may do the heavy lifting, but on its own, it’s useless—it can’t even roll out of the driveway without the rest of the team.

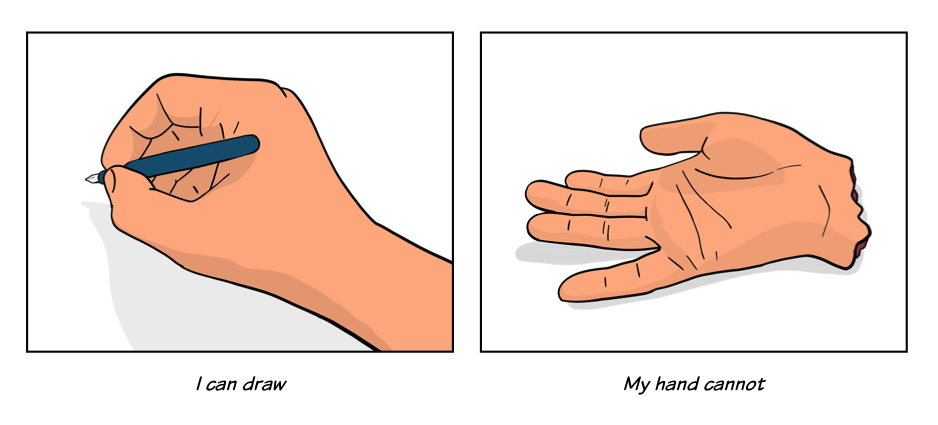

You, too, are a system—you are a whole made up of many parts: hands, feet, eyes, a brain. As a whole you can write, but none of your parts can do it on their own. Try cutting off your hand and placing it on a table; it won’t do much. As a whole you can think, yet your brain cannot. You can walk, yet your feet can’t. So, if you are a system and, as we established, you exist, then it follows that systems must exist. Yes, just your average armchair philosopher at work here!

Then what does it really mean to say “systems don’t exist” ..? We often use the term “systems” not just for physical things like vehicles, but also for models or representations of complex situations or organizations. We build these models based on what we observe and call them “systems,” but the systems as we describe them do not exist. There are aspects we’ve intentionally left out, and there are others we’ve missed simply because they’re beyond our comprehension. Nothing personal—it’s not just us; it might just be how things are. There’s ongoing philosophical debate about whether we can fully understand everything or if some aspects of the universe are simply beyond our reach. Gödel’s incompleteness theorems kindly reminds us that in any formal system, some truths stubbornly refuse to be proven within the system itself. To make things more fun, no consistent system can even prove it won’t contradict itself. In short, you can never really be sure if your system is solid—or just waiting to surprise you with a contradiction!

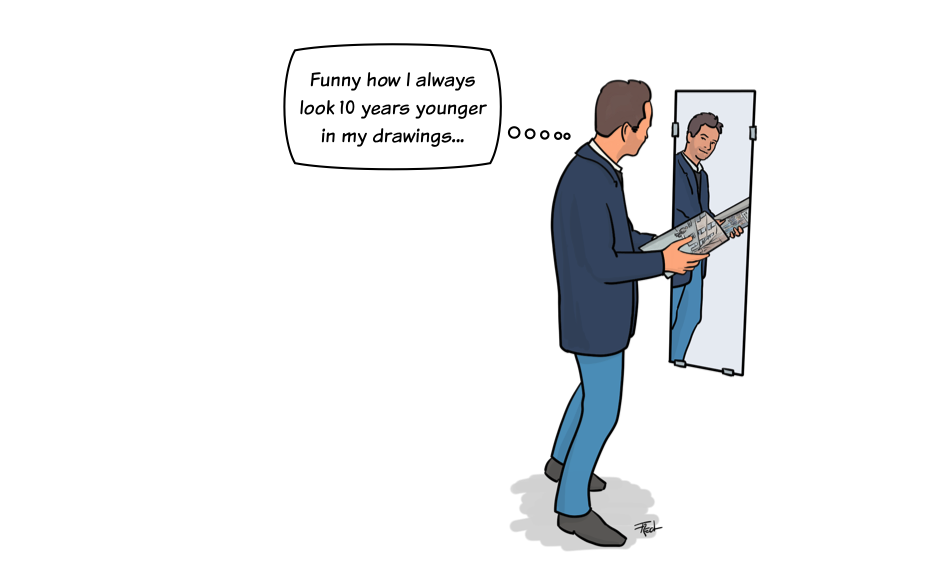

The things we describe may be real, but the model or system we use to describe them is not. The “system” as a concept doesn’t exist. For example, you can create a diagram of a vehicle, showing its components and their connections. Sure, that diagram exists—virtual high-five—but does the diagram capture every single bolt, wire, and drop of fluid? Not at all! It’s an abstraction, and as such, it’s incomplete and inaccurate. When creating a diagram, we filter and focus on the parts of the system that are relevant to the specific purpose the diagram is meant to serve. But the system represented in the diagram doesn’t actually exist. It’s like when I draw myself—I somehow manage to capture only the best parts, conveniently shaving off a few years in the process! Yes, I exist. The drawing of me exists. But the version of me in the drawing? That doesn’t.

Moreover, it’s worth noting that I’m the one creating this drawing. You could make a similar one, but it would naturally reflect your own perspective, interests, and interpretations. Look at the artists below, for example—each brings a distinct style, technique, and choice of materials. Of course, you might say—that’s the whole point of art, to offer a unique perspective. But this applies to all of us in everything we do. We all have our own viewpoints, and this holds true even for things that seem purely objective, like flowcharts, block diagrams, project plans or gantt charts. Even the most seemingly objective deliverables are shaped by the perspectives of those who create them.

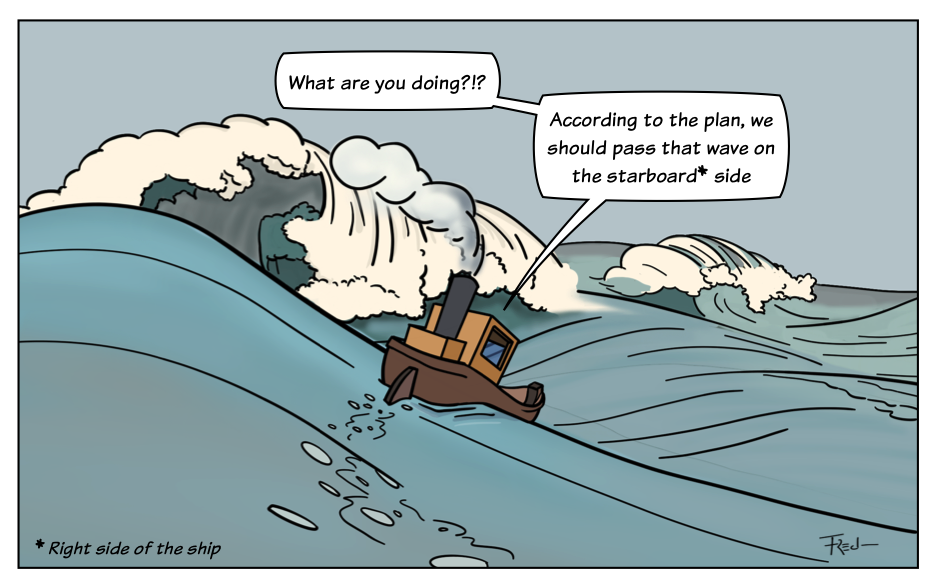

As a project manager, the project plan is one of my key tools. It is important to recognize that the project plan is also an abstraction—a model that documents an often complex situation. An abstraction that captures the interaction and dependencies between components, collectively forming the whole—the project. But it is not reality. Project managers have coined the term “progressive elaboration” to describe the fluidity of the plan; as we progress, we refine our understanding and get closer to the goal. A project plan reflects the current viewpoint and status, the current understanding, offering insight into where we are now and suggesting potential paths forward. When you show someone a drawing, it’s usually accepted as just that—an approximation of something real. But hand over a project plan, and suddenly people act like it’s etched in stone—immovable and unchanging. The Truth, with a capital T. Let’s just say, that may not always be the case, and the project may not completely unfold exactly as originally planned. Yes, please note the understatement.

So, why do we work with these imperfect, non-existent models and system descriptions? Even though they may be abstract or imprecise—and don’t exist in any tangible form—they remain incredibly useful. They provide a shared framework for understanding complex situations, helping us tackle challenges and identify dependencies. Just remember: “they don’t really exist.” They are abstractions and filters, always lacking details and sometimes omitting important ones. It’s crucial to stay cautious, continually question their validity, and maintain a skeptical and humble attitude.

Tomorrow is a new day, and progressive elaboration can easily transform today’s system, model or plan into tomorrow’s scrap paper.