I love baking Apple pie. In fact, that may not be completely accurate. I love eating Apple pie, and I’m willing to put in the time and effort to prepare it. The first time I baked an apple pie was when I was about 8 years old. I was going to spend the weekend with my grandparents and wanted to bring something other than flowers or a simple cake. Printed on the rear of the flour box was a recipe for an original Dutch Apple pie. How difficult could that be? It ended up taking most of the afternoon but was a good investment. It turns out, my grandparents’ appetite for butter and sugar was somewhat limited, which meant I ended up eating apple pie the whole weekend. Best weekend ever!

I’ve been baking, and eating, Apple pie ever since. Baking myself, with others, as a workshop with the team in person when the bakery next door offered the use of their ovens after hours, or with the team remotely during the pandemic. It is nice to bake Apple pie with others, and especially when the other graciously offer to help with peeling apples. Yes, I like Apple pie. But no, I do not like to peel apples.

You know what’s funny? Whenever I bake an apple pie, it always turns out to be a great. Even though preparation never goes as expected, the outcome never is not good (excuse my double negative), but on time, delicious, and a success. You may not believe me. My sister did not, and decided to challenge my beliefs when I visited her recently. Despite her aversion to Apple pie baking and her tendency to normally steer as far away of it as possible, she boldly attempted to make a Dutch apple pie, fully expecting disaster and failure. The outcome was not as expected. She had to admit, the pie was absolutely delicious.

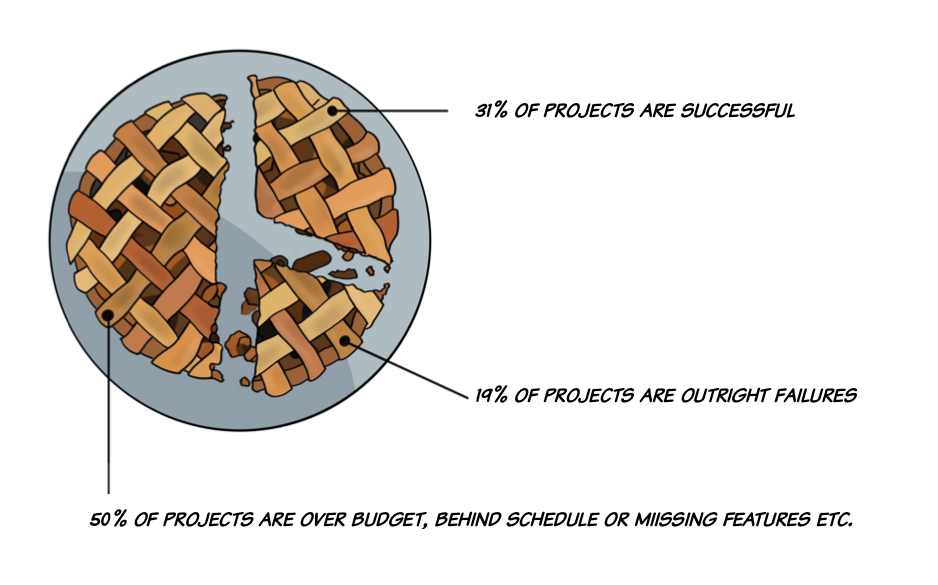

Why is it so difficult to have a successful projects in a business environment? Granted, projects tend to be more difficult compared to baking an apple pie. But we also have more resources, better trained people etc. Yet, only a small proportion of projects are recognized as successful. For example, the 2020 Standish Group’s CHAOS Report (CHAOS 2020: Beyond Infinity Overview. January’2021, QRC by Henny Portman), which analyzes project success rates, has historically shown a “higher percentage of challenged and failed projects”, which is the polite way of saying that many projects are not successful.

In their 2020 report it stated only around 31% of projects are considered successful, 50% are challenged (meaning over budget, behind schedule, or missing features), and 19% of projects are outright failures (canceled or never used). As illustrated by the (Apple) pie chart. If you browse the internet you’ll find similar statistics, indicating that project failure ranges from 20% to over 70%, depending on the context and criteria used for defining failure. Completing a project successfully is not easy.

Apple Pie – as a project?

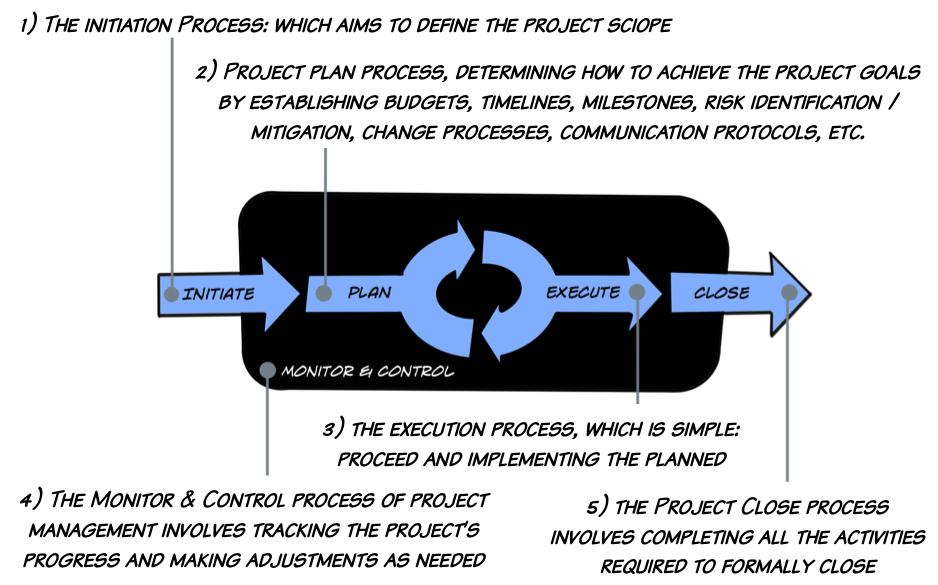

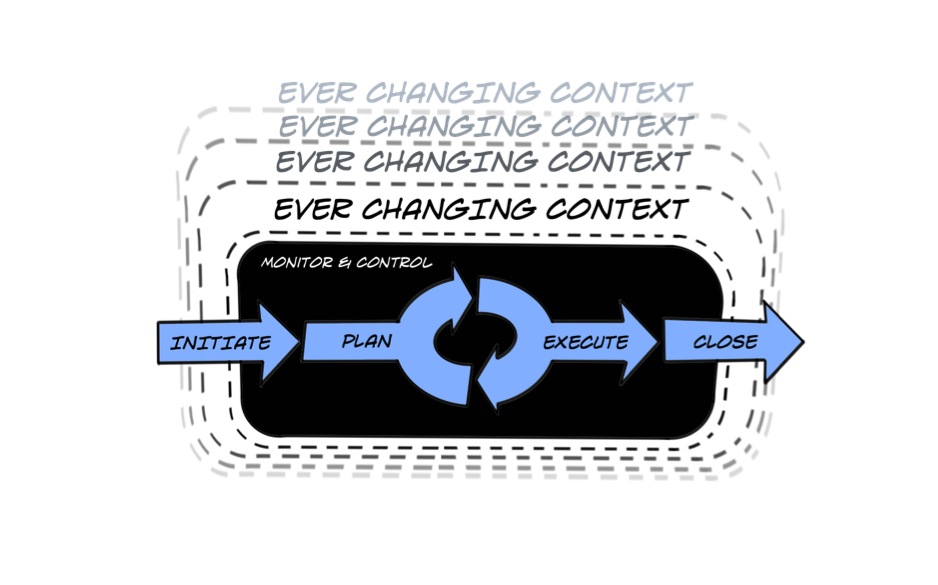

What if we approach baking a Dutch Apple pie as if it was a proper project? For example, shown below is an generic example (after Project Management Body of Knowledge, Fourth edition). It schematically depicts five key processes: 1) Initiate, 2) Plan, 3) Execute, 4) Monitor & Control, and 5) Close.

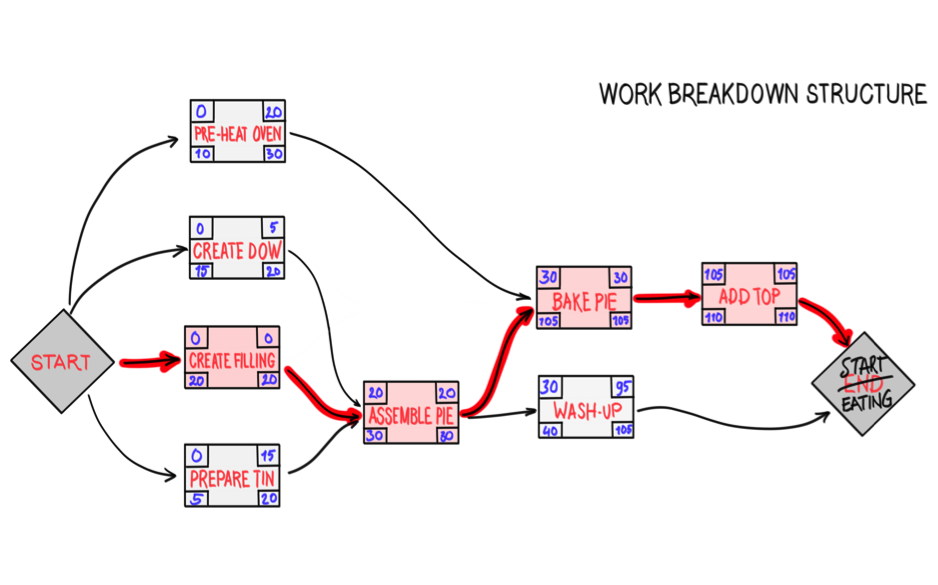

How would this apply to baking a Dutch Apple pie? One of the activities you engage in as part of the planning is the creation of a work breakdown structure (WBS). A WBS is a hierarchical decomposition of the project scope into smaller, more manageable work components. A WBS helps to organize and define the total scope of the project. Basically, “if it is not in the WBS, it is not in the project”. Moreover, as it maps out dependencies between work components, allows you to identify the slack, the critical path, and provides you with a framework for creating the schedule and planning of resources.

Baking an apple pie as a project you may notice at least two things. First, it is not predictable. For example, depicted is a WBS for baking an apple pie. This one is created having the experience of a lifetime baking apple pies and verified with someone who also has some experience. But I am not sure I would be able to accurately estimate these times on a first attempt. And projects – by definition – are unique. You may have transferable experience, it might be similar to something you have done before, but never exactly the same. That is probably why we have invented the concept of “progressive elaboration”. Our understanding is constantly refining and our current plan at best is a a reflection of our current understanding, which still is being refined. In case of baking apple pies, we accept this constant flux of changes. We know this, and deal with it pragmatically. For example, if a few of the apples are not usable and you end up having only one kilogram instead of the required one and a half, you simply cut the apples in larger parts to at least get the volume, or find a smaller tin and serve smaller parts. You may even rush to the shop. Or, for example, starts smelling and looking terrible good after only 50 minutes instead of the required 75 minutes, you might decide to take it out of the oven early. You will do whatever is needed to get an apple pie fitting the event it is intended for.

Such an approach often is difficult when we run projects in a business context, especially in case of larger more complex projects. With a project we assume the brief (the recipe) to be constant. To be fixed. Focus seems to be on delivering on the brief, in the process of which we may loose track of what it is the brief is trying to achieve. Yes, there is a change process to make changes. But making changes is the exception. We tend to focus on executing the plan and treat change as exception, whereas change is more likely to be common and a stable plan the exception.

Second, the context of a project is not a constant, but undergoes constant change. For example, you may set out to bake an apple pie because your sister is visiting and find out your mother and brother are coming along as well, and you decide to look for a larger tin, roll the dough a bit thinner and muscle through the peeling of some extra apples. Ambitions and targets change all the time. The situation may have changed since the project was approved, about 13 months ago. A new competitor has created a new context. Moreover, the context of the context is equally fluid, although it might be less fluid compared project’s immediate context. And then there is the context of the context of the context. As you might suspect, with every context having a context of itself, and every context being in a state of continuous change, if you let me continue, we’d eventually delve into the tiniest shifts in the universe’s early stages and how they could influence our baking of an apple pie. I hear you; “All right, we understand, Fred. It’s an unbroken sequence of changes all the way up.”

Luckily, as you ascend the ladder of nested contexts, at some level, you arrive at a context that, compared to the project’s context, is relatively stable and free of change. While the brief of the project defines the implementation of a new cloud based back-end software, the reason for starting on this journey may be to reduce the number of client calls, which may be one item of a larger journey towards a more self-service based digital approach. Finding the level of context that is relatively stable may assist you in recognizing the value that your project offers, thereby aiding you in sequencing, prioritizing, and navigating any changes or disruptions that might arise from the lower-level context. We are baking an apple pie for my sister’s visit. It may be this afternoon or next weekend, there may be more joining in the fun, but apple pie with my sister is what we are going for here.

In short, as far as I can see when baking an apple pie we expect and pragmatically deal with the changes because we have no difficulties to see any disruptions in the context of the larger ambition. With projects this often is more difficult to understand the project’s invariant value. Understanding the project’s value and ensuring all who participate has a view on what what the outcome of the project is aiming to achieve, opens up many ways to solve problems creatively. It provides the context that allows us to use new strategies to handle issues, and allowing the team to connect what they do with the project’s purpose. And yes, I know. Seasoned project managers will read this and ask themselves “so what is new?” And I agree. But I also am continuously confronted with the situations where an appreciation for constant change and an understanding of over arching purpose is as rare as a failed apple pie.

Prologue – Towards the end of last year, I gave a presentation exploring systemic thinking as the cornerstone of project management challenges. The process of preparing for this presentation was immensely enjoyable, so much so that it inspired me to create a complementary handout titled “Project Management & the Fine Art of Baking Dutch Apple Pie” which, with the experience of the presentation and feedback from participants, transformed into a small booklet spanning roughly A5 size and comprising around 140 pages (see pages of the book, here).

For those intrigued, you can find the booklet on Amazon (Kindle and paperback), or you can direct message me for a complimentary copy, as I still have a handful remaining (while supplies lasts).

Reviews / Media

- Feb 2024 – Linkedin Post by Janet Kistler: Book Review: Project Management & the Fine Art of Baking Dutch Apple Pie – Indulge in the delightful chaos of project management while savoring a slice of homemade apple pie with “Project Management & the Fine Art of Baking Dutch Apple Pie.” With side-splitting anecdotes and practical advice hotter than a fresh-out-of-the-oven pie, this book is your recipe for success in the wild world of deadlines, scope creep, and Monday morning coffee crises. Whether you’re a seasoned pro or a newbie, grab a fork and dive into this comedy masterpiece. Just be sure to save room for dessert—and for laughter!